Computational Systems Biology

Biology is the study of life. Its goal is to gain comprehensive knowledge of how cells and organisms work, individually or in groups. Systems biology is a new speciality area that actually has exactly the same goals and purposes as general biology, namely, to understand how life works. But, in contrast to traditional biology, systems biology purposes these goals with a whole new sets of tools that come from mathematics, statistics, computing and engineering, in addition to biology, biochemistry, and biophysics. System biology utilizes these tools to determine the specific roles of the many diffirent components that we find in living organisms, how these components interact with each other, and how they collaborate to create and support life. A prominent feature of systems biology is its heavy use of the enormous capacity of modern computers to store, manage, analyze and interpret huge amounts of data. In addition, systems biology readily recognizes that detailed knowledge of the molecules and structure of the life is crucial, and that traditional research absolutely needs to continue, but it stresses the point that this knowledge alone is insufficient. We need methods of putting the parts together, new ways of thinking and new methods of analysis that allow us to understand how the building blocks interact and what controls and regulates these interactions, and we need these studies to be done on huge numbers of observations simultaneously.

The Scientific Revolution of the 17th centry brought real change with two great advances in biology. First, the microscope was invented and paved the way to an entirely new world of life: microbiology. The second novelty was a firm rule set for valid research, called scientific method. This method demands that exact science follow well-defined steps of formulating a hypothesis, testing this hypothesis with experiments, analyzing the results, and based on the results and their interpretation, formulating a new hypothesis. Systems biology improved this methodology complementarily, and lead to major breakthroughs, which we will try to explain with specific examples later in this post.

The –omics revolution

In the past, experiments were time consuming and expensive and data were therefore often scarce. The so-called –omics revolution has changed that to a point where we often have so many data that we can not make sense of them and need to resort to sophisticated computing methods. As “omics” is not really a word, but rather a suffix that has been attached to various biological terms to indicate “all of it” or “a lot of it”. The best known example is genomics, which means studying the structure, function and evolution of genes; not one gene at a time, as it used to be done a few decades ago, but for all genes at the same time.

The –omics revolution has not only generated huge datasets, it has turned the tried-and-true scientific method on its head. The central position of a strong hypothesis has vanished, and the new mindset is exploratory data analysis, which were translated into the lax mandate: “lets see what’is out there and then we will try to figure out what it means”. In contrast to the traditional scientific method, there is no hypothesis that gene X or gene Y might have something to do with that particular cancer, but rather all genes are examined in the hope of detecting patterns. Because resulting datasets consists of thousands of data points, they are evaluated with computational methods of statistical machine learning, which reveal patterns in the data.

To summarize this intro section by comparing the traditional and new scientific method of experimental (systems) biology

The traditional scientific method of biology

- Make an observation

- Ask a question regarding the observation

- Do background research to see what is known about the question

- Refine the question to a point that it can be formulated as a hypothesis

- Design an experiment to test the hypothesis and execute it

- Analyse data resulting from the experiment and determine to what degree the results support hypothesis

- If the results do not support the hypothesis, go back to 2,3, or 4

- If the experiment results do support hypothesis, new insights are gained, Share these insights with the scientific community

- Usually new insights lead to additional questions. Formulate new hypothesis that target these questions

The new scientific method of experimental systems biology, applied to a disease.

- Identify an interesting phenomenon, such as a disease

- Decide whether protemics, or metabolomics is most promising

- Perform the same –omics analysis of genes, proteins and/or metobolites with a sample from a healthy person and from a person with a disease.

- Collect significant diffirences between corresponding measurements in the two samples, using methods of machine learning

- Assemble these diffirences into normal and disease profiles

- Formulate hypothesis explaining the differences between these profiles

- Perform traditional experiments testing the most promising hypothesis

- If the results do not support the hypothesis, go back to 2,3 or 6.

- If the experiment results do support one of the hypothesis, new insights are gained and should be shared with the scientific community

Data, Information, Knowledge, Understanding

The new methods of –omics biology, combined with more traditional experiments, have the capacity of generating more high quaility data than ever before. So, why is not that sufficient? Before answering this question, lets explain what is the difference between these terms

- Data: Data are discrete, objective facts, often without a context. Lets say you read “rainfall at the airport was 2.6 centimeters”. You dont know what does that mean, is 2.6 centimeters a lot?

- Information: Generally information consists of processed data augmented/enriched with metadata which consists of such meaning, together with some context and background.

- Knowledge: Is mixture of synthesize information, context, experience and even value judgement. It explains how the information was obtained or generated, recognizes patterns in information, often procedures for assessing a situation, and guides expectations regarding the future

- Understanding: Understand interprets the knowledge. It provides casuality and rationale for a phenomenon, detail and pattern in data. Understanding helps us explain why something is the way it is.

Statistical Machine learning helps us to gain the knowledge and understand it by using given data.

Machine Learning (ML)

ML is a scientific field that studies datasets by combining statistics with heavy-duty computing. The main goal of ML is to train computer programs (algorithms) to find something in a dataset that had not been known before, such as an association between two types of data. The accuracy of findings steadily improves as more data becomes available.

ML requires training that can happen with or without human supervision. In the former case, the human supervisor gives the algorithm a large dataset, lets say, containing data from healthy individuals and from individuals with lung cancer, informs the computer which individuals have cancer and which dont, and instructs the algorithm to find features or patterns in the dataset that distinguish healthy from diseased individuals. In the latter case, algorithm learns without human supervision. It does not know which individuals actually have cancer and which dont. Instead, the algorithm is asked to determine whether there are any significant patterns in the dataset.

Interdependencies of biological systems

Biological systems are super complex. In this part, I will try to write about some of the complexities in different biologies systems and how computational systems biologycan help to understand them using statistical machine learning methods.

Even the simplest of organisms rely on uncounted molecular processes that allow them to thrive, propagate, and respond threats from predators, parasites, and the environment. They contain thousands of genes defining each organism’s set of functions and features; proteins that provide structure, control biochemical reactions, and serve as means of transporting molecules; metabolites for energy and other purposes; many signaling mechanisms that regulate all aspects of life. All of these components are interacting with each other continously, and at a molecular level this organization is captures in central dogma.

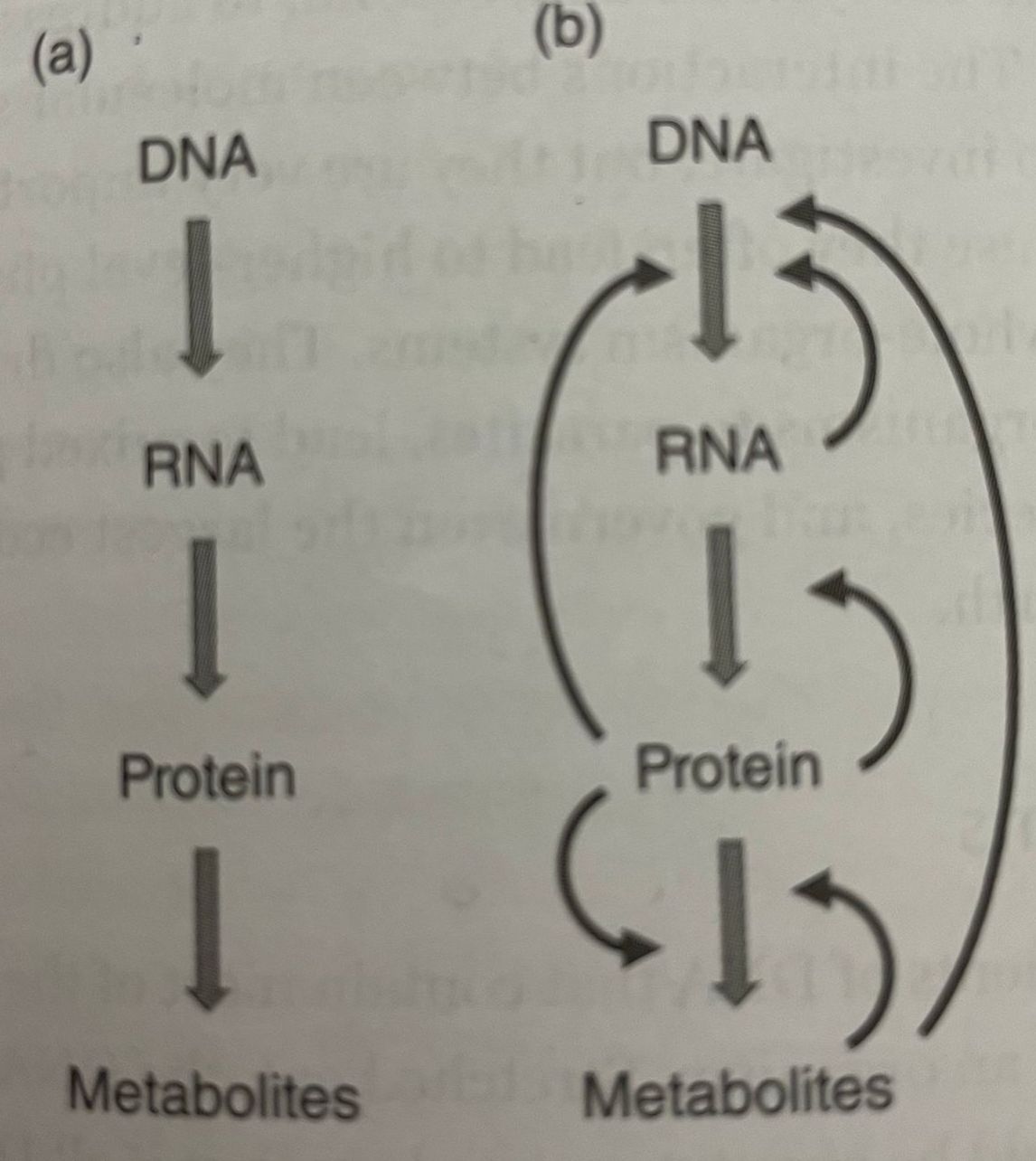

Central dogma holds that the flow of information in the cells starts with genes (DNA sequences), which are transcribed into messenger RNA (mRNA), which in turn translated into proteins. Proteins play structural and signaling roles and control the conversion of food into energy and into metabolites, that is, the numerous and diverse chemical compounds required for life. However, the information flow is regulated in multiple ways. Some proteins serve as transcription factors, which control the transcription of genes into mRNAs. Some of RNA can regulate or even stop the transciption of specific DNA sequences. Metabolites can trigger or prevent the expression of specific genes. The consequence of these insights is that the simple one-way process represented in central dogma is in truth much more complicated: information flows through a higly regulated systems with many feedback signals.

Gene Systems

As we learned in the previous part, DNA is transcribed into messenge RNA, which is subsequently translated into protein. In these two processes of transcription and translation, combination of three DNA nucleotides uniquely represent three RNA nucleotides, which in turn represent one of the amino acids that will ultimately make up this protein. It is important to know which groups of genes in multicellular organisms are transcribed under particular conditions and in which cells. This type of coordination is accomplished by transctiption factors and a number of regulators, which are usually proteins or RNAs that themselves are the products of gene transcription. (Pretty comlicated).

Proteins

Every organism is totally dependent on its genes because they contain most of the information for survival and propagation. But information alone is not sufficient, and actual work is required to thrive. Proteins are the true workhorses for most of the jobs an organism requires. They are at the core of biophysical structures; they serve as transpost engines, manage all the biochemistry that converts food into energy and into the compounds the body needs.

Proteins are large molecules consists of long chains of chemical building blocks, called amino acids. Nature uses twenty diffirent amino acids for proteins, which does not sound much, but permits huge number of diffirent proteins. Most current research activities in this restricted domain fall into three categories: availibility ad location, chemical structure, and function

Research in the first category addresses questions regarding the amounts and localization of proteins under diffirent conditions. Some questions it tries to answer are:

- How do the amounts of proteins differ between a cancer cell and a normal cell of the same tissue?

- If a physical or chemical conditions in a cell’s environment change, do some proteins move to diffirent locations, if so where do they move and what are the consequences?

The second category addresses questions of protein structure. Each amino acid in a protein has its particular chemical and physical properties, depending on its atomic composition and electric charge, which may be positive, negative or neutral. If many amino acids are linked together in chain, these properties cause the protein to bend and fold into complicated three-dimensional structures, such as spirals and barrels. The three-dimensional structure, together with the surrounding chemical milieu, is responsible for the function of the protein. It would therefore be very helpful to predict a protein’s three-dimensional structure from its sequence of amino acids, which we typically know from the gene sequence that codes for it. AlphaFold project from DeepMind, helped a lot to understand the protein folding.

The third category of the protein research focuses on the function of proteins. For instance, proteins are critical palyers in essentially all diseases, whether as signal receptors, enzymes, transporters or something else.

Note: While our focus here is on the central dogma, we must not forget that proteins are also responsible for the transport of compounds between cells and through the bloodstream, that they drive our immune system, and that they permit the function of muscles, thereby allowing movement, including the regular contractions and relaxations that govern our heart, lungs and digestive system.

Signaling

The fine-tunned coordination of systems within each cell or organism requires that their parts must “know” what is happening in other parts, at least to some degree. This sharing of information is called signaling, signal transduction, or signal transmission. For instance, touching a hot stove is perceived by sensors in the fingers, the information is sent via nerves to a spinal cord, which send back signals to the arm muscles instructing them to remove the hand from the stove; all in a fraction of second. This type of signaling through nerves involves chemical and electical processes. At the cellular level, signaling can be achieved with proteins, small molecules like calcium or electricity.

A widely found signal transduction system is combination of a receptor with a protein-based signaling cascade. The receptor itself is located in the cell membrane with one part of it sticking outside the cell and the opposite part reaching into the inside. The outside component is able to bind to appropriate signalling molecules outside of the cell, which are collectively called ligands. These ligands may be of very diffirent types, but are specific for a given signaling task. Once a ligand binds, the inside conformation (molecular shape) of the receptor changes, thereby serving as an internal signal turning on a signaling cascade. Computational research in this area falls into two groups:

- how the various cascades are composed, how they interact, and how signals travel throughout a cell.

- What are the dynamics of known cascades.

Metabolic pathways

Metabolic pathways are chains of chemical reactions that convert metabolites into other metabolites. As an example, a chain of ten reactions converts glucose from food into the common intermediate metabolite pyruvate, which is subsequently used in numerous other reactions. Each biochemical reaction uses a substrate (e.g glucose) and converts it into a product (e.g pyruvate) which then becomes the substrate of the next reaction. Specialized enzymes facilitate most of these reactions by acting as catalysts. Metabolites may be seen as the last components of the central dogma; indeed, the pathways converting them into each other are often the ultimate targets of changes in gene expression.

It is often at the level of metabolites that diffirences between health and disease manifest. Diabetes is associated with an imbalance of glucose in the bloodstream. Parkinson’s disease results from low level of the brain chemical dopamine, and cancer cells rewire their metabolism for energy production and proliferation. Most biochemical reactions are executed by enzymes, whose amount and chemical and physical features determine how fast a substrate is converted into a product. Most enzymes are very specific for the task and execute only a single reaction or at most few reactions with similar substrates, although they are exceptions.

From the viewpoint of controlling a system, like a metabolic pathway system, a very important feature is the option of regulating the fluxes, that is, the amounts of material flowing through each reaction at a given time. A prominent tool is feedback inhibition: If a lot of end product of a pathway is already available, the end product itself send a signal to the first step of the pathway, “instructing” it to slow down or even stop. This instruction is accomplished by affecting the enzyme that is responsible for the first step of the pathway. Two very frequent mechanisms are competitive inhibition and allosteric inhibition. In the former case, the end product has a chemical structure that is so similar to the substrate of the first step, that it competes with it for the enzyme, thereby tying up some of the available enzyme molecules and slowing down the reaction. In the latter case, the end product, or some other metabolite, can bind to some location on the surface of the enzyme and by doing so change the activity of the enzyme with respect to the substrate. In both cases, the enzyme activity is reduced or stopped.

How Computational systems (ML) can help?

Understanding the functionality of these types of systems/networks (gene systems, protein, metabolic pathways) is an important task of computational system biology. Sincethey(functionalities) can not observed directly, they must be inferred from data with methods of ML. The key step of a computational network inference is a sophisticated statistical analysis of data indicating that certain genes are co-expressed, which means they are transcipted into RNA under the same or similar conditions, such as heat, pressure, or exposure to some chemical in the case of bacterial cell. If the same two genes are often co-expressed or silenced at the same time, the hypothesis is that they are controlled by the same transciption factors and regulators. I believe, one day mathematics and computation will be capable of reliably predicting, manipulating and optimizing biomedical systems for the advancement of medicine, drug development, biotechnology and productive and sustainable stewardship of the environment.

Resources

- Systems Biology: A very short introduction